Construction Defect Litigation

What do construction defects consist of?

(There are hundreds of defects that can cause damage to a property. This is a limited list of common defects.)

- Stained drywall at window sills and ceilings

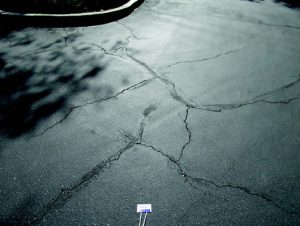

- Cracks along streets, common area slabs or pavers

- Frequent and excessive cracks at drywall or stucco

- Leaks or staining at or around common area planters

- Staining or discoloration below patio decks and at entry landings

- Excessive cracking at interior tile flooring, garage slabs or patio areas

- Water intrusion though windows or doors

- Cracking or step cracking at perimeter block walls

- Soil erosion or slope creep/movement

- Poor drainage at surrounding landscape and yard areas

- Excessive water pressure or fire sprinkler pressure at meter

- Water ponding at patios, decks, roof, or streets

- Waterproofing failure at exterior or property

- Excessive tile roof cracks

What does a construction defect look like?

(Click Photos To Enlarge)

FAQ’s

Usually in a construction defect action you can recover for the cost of repair, or the value of the reduction in value of the property, whichever is less, subject to certain factors that may increase your recovery. Because a community association is generally required by its CC & R’s to maintain and repair common areas, the typical measure of damages is the cost to repair. Other potentially recoverable damages include the cost of investigation, relocation and storage, and other costs recoverable by contract or statute. Punitive damages are also available in cases in which fraudulent misrepresentation or fraudulent concealment is found.

Generally speaking, a construction defect is a deficiency in the design or construction of a building or structure. The cause of the condition can be the result of faulty design, materials, and/or workmanship. It is important to note that structures include single-family residences, condominium units, as well as the common areas a homeowner’s association is obligated to maintain.

Some examples of construction defects may include: significant cracks in the slab and/or foundation; unevenness in floor slabs caused by abnormal soils movement; leaky roofs, windows, or doors; moisture problems due to improper drainage and/or waterproofing; faulty or corroded plumbing; doors and windows that bind and are difficult to open and close; and cabinets or counter tops that are separated from walls or ceilings. (This is not an all-inclusive list.) Any condition in your property that makes it unsuitable for its intended use may be considered a defect. (California Civil Code 896)

Deadlines to bring construction defect claims are determined by statutes of limitation. In California, homes that have a substantial completion date or close of escrow date after January 1, 2003 are governed by Civil Code Section 895, et seq. (“SB800”). This statute contains one-, two-, four-, five-, and ten-year statutes of limitations. The following time limits are applicable to homes built after January 1, 2003:

1 year

- Noise (from original occupancy of adjacent unit)

- Fit and finish warranty

- Irrigation and drainage

- Manufactured products

2 years

- Decay of untreated wood posts

- Landscaping systems

- Dryer ducts

4 years

- Electrical systems

- Cracks in exterior hardscape, pathways, driveways, landscape, sidewalls, sidewalks, patios

- Corrosion of steel fences

5 years

- Deterioration of building surfaces due to paint or stain

10 years

- If not specifically set forth in SB800, no action may be brought to recover under SB800 more than 10 years after substantial completion but not later than the date of recordation of a valid notice of completion.

Board member duties include properly handling potential construction defect claims. Civil Code Section 1365 (f) (1) provides that the scope of duties of a director includes the decision to conduct an investigation of the common area for latent defects prior to the expiration of the statute of limitations. The Board’s decision whether to investigate defects is one that the Board should make after exercising reasonable inquiry as required by Corporations Code Section 7231 (a) and relying on the advice of consultants such as architects and engineers, as well as legal counsel, as set forth in Corporations Code 7321(b).

Satisfying these responsibilities used to be much easier for Board members. Before the passage of Civil Code Section 895 et seq, (commonly known as SB 800) generally, a Board had ten years from completion of the project to bring a construction defect lawsuit against the builder (period was tolled while builder controlled the Board). If the board waited more than 10 years, the association generally lost its right to recover. This sometimes resulted in a Board having to levy large special assessments against its members to repair defects. The Board members’ duties in this regard are much more complex because there are now different statutes of limitations for different defects. For example, there is now a one-year statute of limitation for drainage and irrigation defects. There is now a four-year statute of limitation for certain plumbing defects and some hardscape and driveway defects. As a result, Board members often have to confront defect issues immediately upon joining a Board.

Both SB 800 and Calderon (Civil Code 1375, et seq,) provide an important process allowing the Board to stop (toll) the clock from running, while investigating potential construction defects without actually filing a lawsuit. Calderon provides for a six-month tolling of the statute of limitations while evaluating a potential defect case. SB 800 permits the tolling of the statute while the builder considers making a repair. This can often take several months.

Finally, Civil Code Section 1375, et seq. does not permit the Board of Directors to delegate the decision of whether to file or not file a lawsuit to the association members. This is the sole duty and responsibility of the Board of Directors as set forth in Civil Code Section 1365.7

Yes. Typically, the association’s CC & R’s provide for special procedures that must be followed prior to pursuing legal actions for defective construction. These procedures may include requirements of notice to be provided to the membership, sometimes even requiring that a vote of the membership be held prior to engaging legal counsel. You should review the requirements of your CC & R’s, and discuss them with qualified legal professionals prior to commencing any legal action.

In addition to the CC & R’s, in California, special procedures are required to be followed by California statute. One of the procedures is commonly known as the “Calderon Process”, and is generally required to be fulfilled prior to filing a lawsuit for defective construction. This process includes notices, exchanges of information, inspections, and mediations. Although intended to expedite claims for defective construction, the process can be manipulated by builders to add additional delay to resolving the issues if not diligently monitored by experienced professionals who understand and have experience with the process.

Another process in California that generally applies to residential properties sold for the first time after January 1, 2003, is commonly referred to as “SB 800”. This process concerns claims for failure of residential structures to comply with the “functionality standards” discussed above. Prior to an individual or association filing suit for claims of violations of “functionality standards”, the builder must first be given notice of the defects and have an opportunity to repair the conditions. The builder’s “right to repair” process is extremely technical and contains many traps for the unwary consumer in which the builder can substantially delay the process. We recommend that you retain qualified legal assistance with expertise in construction well before any attempt is made to initiate the legal process, to ensure that your dispute not only includes all appropriate claims, but also moves forward as expeditiously as possible.

No. Generally inspections and testing can take place while the units are occupied.

There are a variety of ways to structure the fee arrangement, from paying for professional services based on time worked and costs incurred, to a contingent fee agreement. In a contingent fee agreement, you do not pay legal fees unless and until there is a recovery. Other costs of the litigation may be charged to the client, but may also be advanced by the law firm and recovered from proceeds of case resolution. Some of the investigation and analysis expenses can also be recovered at trial, assuming the case goes that far.

Your CC & R’s may also provide that you can recover attorney’s fees in addition to the damages.